Dynamic seismic risk communication and rapid situation assessment in face a destructive earthquake in Europe

Rémy Bossu, Istvan Bondàr, Maren Böse, Jean-Marc Cheny, Marina Corradini, Laure Fallou, Sylvain Julien-Laferrière, Frédéric Massin, Matthieu Landès, Julien Roch, Frédéric Roussel and Robert Stee – Euro-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC).

On December 29th 2020, a strong earthquake with a magnitude of 6.4 shook the city of Petrinja, 45 km south of the capital city of Zagreb. Eight people lost their lives. In March 2020, eight months before the Petrinja event, an earthquake with a magnitude 5.3 damaged the capital Zagreb to a similar extend. Due to the Zagreb earthquake and its aftershocks, the LastQuake app developed at the Euro-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC) had a high penetration rate of 7% in the country at the time of the Petrinja earthquake. In addition, EMSC had released a new website for mobile devices to optimise crowdsourcing of felt reports a few weeks before the Petrinja earthquake occurred. These specific circumstances made the Petrinja earthquake an ideal test case for dynamic risk communication and the rapid situation assessment tools developed by EMSC within the RISE and TURNkey projects. RISE (Real-time earthquake rIsk reduction for a reSilient Europe) is a project funded under the same H2020 call of TURNkey. Both projects aim at reducing future human and economic losses caused by earthquakes in Europe.

The Petrinja mainshock was detected within 66 seconds through a surge of EMSC website traffic and 11 seconds later from concomitant LastQuake app openings. These crowdsourced detections initiated a so-called “Crowdseeded seismic Location” (CsLoc). It is a method that exploits the geographical information of crowdsourced detection to select the seismic stations likely to have recorded the earthquake. The method also uses the time information to identify observed arrival times likely associated with this earthquake to perform fast and reliable seismic location. The automatic CsLoc was published 98 seconds after the earthquake and it was located 8 km away from the location that was manually reviewed afterward. EMSC received more than 2000 felt reports in the first 10 minutes, out of a total of more than 15000, before its servers started to experience significant delays due to the high traffic. These initial felt reports were sufficient to evaluate the epicentral intensity at VIII (for a final epicentral intensity of IX), i.e. damaging levels. Furthermore, they confirmed the heads-up from the automatic impact assessment tools “EQIA” (Earthquake Qualitative Impact Assessment). About 140 geo-located pictures were crowdsourced showing the effects of the earthquake. EMSC shared all the information on rapid situation assessment with the ARISTOTLE (All Risk Integrated System Towards Trans-boundary holistic Early-warning) group in charge of preparing an impact assessment for the European Civil Protection Unit within 3 hours of the event.

-

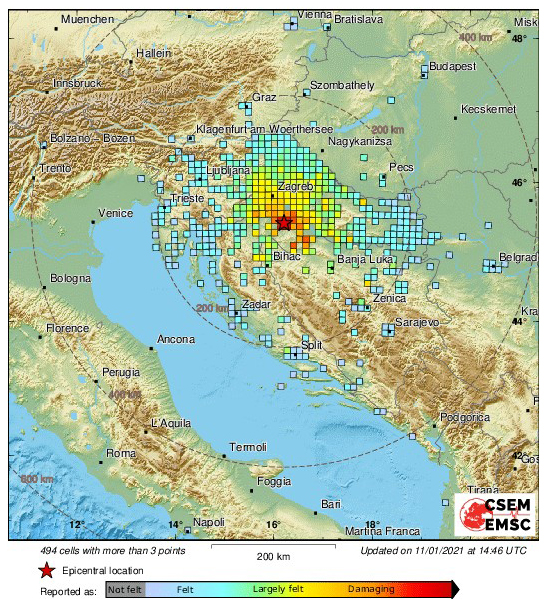

Automatic clustering of individual felt reports collected for the Petrinja (Croatia) earthquake in 10 km grid cells.

Only cells containing a minimum of 3 reports are represented through their average intensity value.

A posteriori determined rupture orientation and position from felt reports collected within the first 25 min using the FinDer software developed at ETH Zurich are in good agreement with fault orientation from tectonic settings and aftershock distribution. This approach will be tested further in operational conditions in the coming months.

The large volume of collected felt reports accelerated the cooperation with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) to integrate them in USGS global ShakeMaps and define common geographical clustering approaches of individual reports.

Beyond these scientific results, a significant effort was devoted to complete automatic information published on Twitter @LastQuake by answering questions and explaining the reasons for service disruptions observed after several main aftershocks occurred. All communication was performed in English. We retweeted many of the tweets from the Croatian seismological institute and referred to them as much as possible. Questions followed according to the time evolution already observed after other damaging earthquakes. First, people were interested in the expected impact, then in the possible evolution of the seismicity, in the earthquake prediction (with the traditional confusion between forecast and early warning), and finally whether human activities (in this case hydrocarbon exploitation) could have caused the tremblors. During this period which lasted about two weeks, there were also many questions about seismology, such as the meaning of the magnitude, intensity, or the reasons for magnitude discrepancies between institutes.

It is difficult to evaluate the impact of this direct public communication effort quantitatively. Due to the English, in fact, only part of the population was reached. However, there are elements that seem to indicate that Twitter users appreciated our effort. The number of tweets viewed reached 9 million the day of the mainshock, and an average of 4.8 million over the first seven days. Again, this demonstrated the strong interest of the public in receiving information after a damaging earthquake and during an aftershock sequence. Tweets explaining that earthquake prediction does not exist were liked 700 times. Many users reported that getting rapid information and direct answers to their questions was the key to decrease their anxiety. This public interest led to tens of interviews in national and regional media. But perhaps more meaningful in terms of public appreciation, EMSC collected more than 2000€ from individual donations and received many offers for technical support in relation to our service disruptions from both IT specialists and companies. This experience also underlined the many improvements that still need to be done, from strengthening our IT infrastructure to hierarchize information during an aftershock sequence better. In general, the great interest shown by the public in Croatia in receiving information after the Petrinja event demonstrates a strong need for dynamic risk communication. Moreover, it proves that crowdsourcing can significantly improve the capacity for rapid impact assessment.